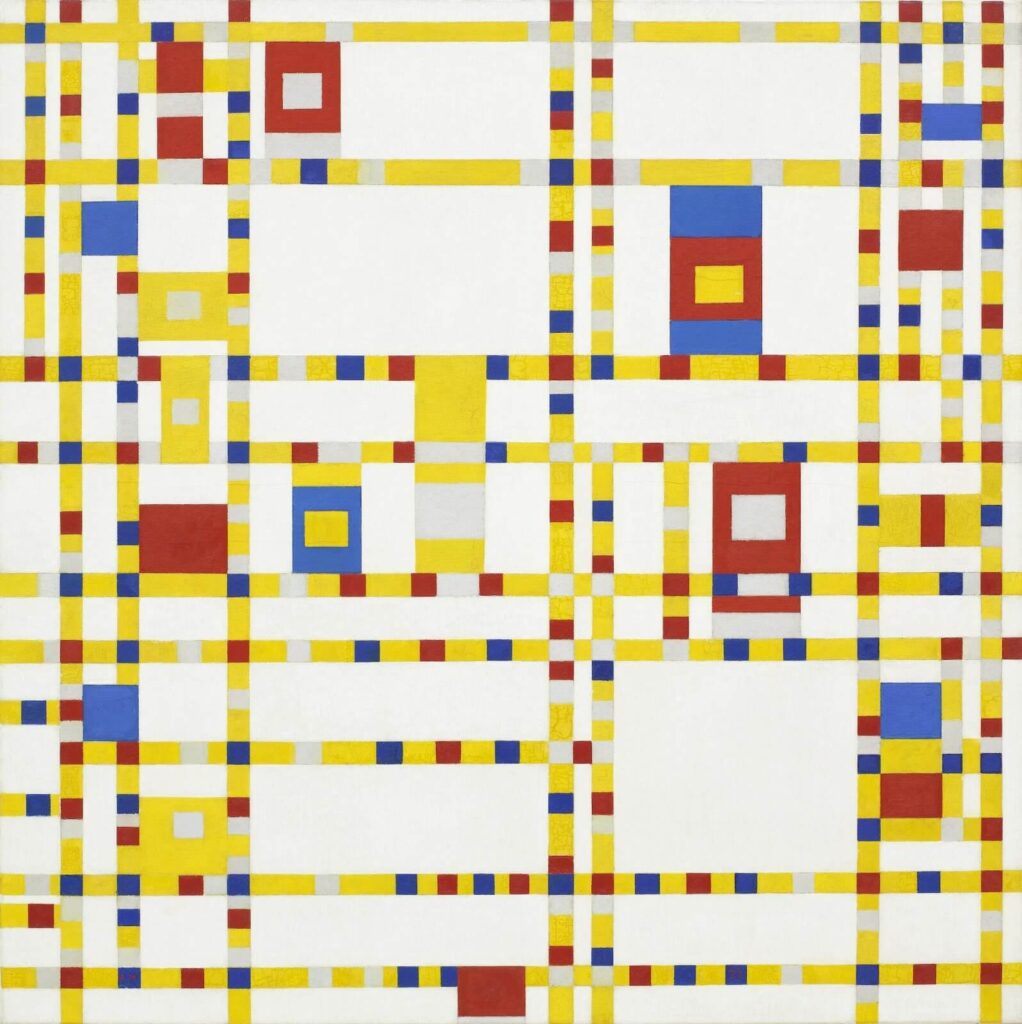

TICC Classes: Conversation as Adventure

Albert Murray understood the jazz or blues musician’s improvisations as on-the-spot responses to moments of musical crisis. He asserted that the superlative improviser requires knowledge of the history of what others have accomplished on her instrument in order to respond creatively in these moments of crisis… the break in the ongoing flow of music…the moment of “greatest jeopardy,” which also represents a moment of great opportunity, when you “write your signature” on reality. And just as the jazz musician requires knowledge of the musical past to respond adequately in that moment, human beings also require knowledge of the “wisdom and mistakes of the ages” to respond creatively to the crises of their own times. What other forms of human life are possible? How have human beings in other times and place answered questions like, ‘how should we live together? or: ‘what is of greatest value’? Documents of human culture – novels, poems, scripture, music, cave paintings – pass down that wisdom and error. Without this human data to self-consciously respond to, our imaginations are frozen, and we compulsively repeat variations on whichever themes are most audible to us in the surrounding world. Careful, unpressured listening and attention to documents from all of humanity’s present and past, from the Popol Vuh of the K’iche’ Maya to Dostoevsky’s Notes from the Underground, is therefore central to coming to understand oneself, one’s society, one’s own time – and responding creatively in moments of disjuncture.

A 5,000 Year Conversation

Version of this course are taught for both adults and also high school age students, who are interested in expanding their horizons, by encountering voices from other times and places than our own. It is patterned after the first-year sequence developed by TICC teachers at Pacific Lutheran University for the past decade. (for interested students, 16 years and older)

What does it mean to be human? How should humans respond to the socio-political, the historical, the natural, the animal, and the sacred worlds? Are these worlds characterized by permanence or change, oneness or diversity, hospitality or hostility? Why do these questions arise for us as humans? How could we go about answering them? To investigate these questions and more, we will comb through the experience data of humanity preserved in writings from across the ancient world. Possible texts include The Epic of Gilgamesh, The Hebrew Bible, The Story of Sinuhe, The Dao De Ching, The Iliad or the Odyssey, The Popol Vuh, Plato’s “Apology” or other dialogues, The Sunjata, etc.

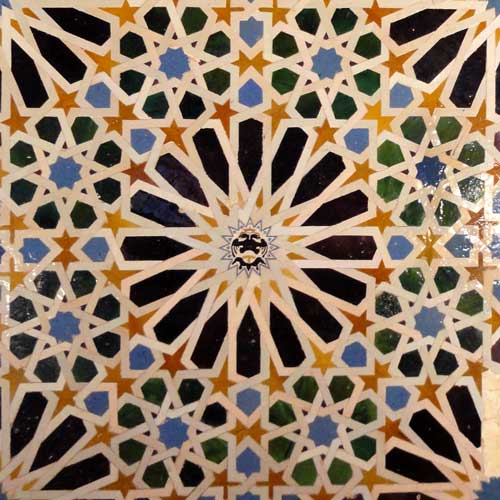

Creation Narratives of the Americas and their Resonance

For thousands of years, inhabitants of the Americas have been telling stories about how the world began, what a human being and human order are, and how to deal with crisis, among many other matters – creating a body of texts remarkable in their scope and vitality. These creation stories of the Americas work together in important ways, corroborating each other in terms of cultural experiences extending long before contact with Europe. Subsequently, writers, painters, and other artists in what have become the nation-states of the American continent have taken up elements of these stories to address their own concerns, in quite different times and places. Together, we will read these some of the original creation stories, along with contemporary work which continues them, and consider what we might learn from them today. Possible texts might include: The Popol vuh: The Mayan Creation Account; Watunna: An Orinoco Creation Cycle; Diné Bahané: The Navajo Creation Cycle; short stories by Julio Cortázar, José Luis Borges, Rosario Castellanos, and Juan Rulfo; artists such as Diego Rivera; films such a Cuarón’s Roma, and Tommy Orange’s novel There There.